Statistics on men’s mental health and wellbeing

Share:

Mental health statistics

Psychological distress

10.2% of men (aged 15+ years) surveyed in the Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora’s 2023/24 New Zealand Health Survey reported high or very high levels psychological distress in the four weeks prior to the survey, compared to 15.5% of women, and 13.0% of the general adult population.

There has been an upward trend in high or very high levels of psychological distress among men since 2011/12, when 3.7% of men reported high or very high levels of psychological distress.³

Māori, younger adults, disabled people and those living in socioeconomically deprived areas are most affected by psychological distress. Māori men are affected slightly at slightly lower rates than Māori women.⁴ ,⁵

Mental health service access

In 2023/24, a total of 176,390 clients accessed mental health and addiction services. Of these, 88,698 (50.3%) were male, and 87,692 (49.7%) were female⁶ .

Figures on unmet need for mental health services show 8.9% of men surveyed in 2023/24 experienced an unmet need for mental health and addiction services in the previous 12 months, compared to 12.1% of women (up from 5.3% and 9% in 2022/23, respectively)⁷.

Hazardous drinking

Alcohol and substance use can have negative impacts on wellbeing. In 2023/24, 22.2% of men have hazardous drinking patterns, compared with 11.2% of women and 16.6% of the general adult population. 38.4% of Māori men are hazardous drinkers, as compared with 21.4% of Māori women. 22.9% of Pasifika men are hazardous drinkers, as compared with 9.1% of Pasifika women.⁸

Suicide and self-harm

Two sets of suicide figures are presented here – unconfirmed suspected suicides, which are more recent, and confirmed figures which have been through the Coronial process.

The Ministry of Health’s figures in 2023/24⁹ show that:

- There were 445 male suspected self-inflicted deaths, in comparison to 172 female. In short, nearly 75% of suicides over this period were men. The rate of suspected self-inflicted deaths for males was 15.9 per 100,000 males, which was a statistically significant decrease from the average of the last 14 financial years.

- The rate of confirmed suicide deaths for males in 2019-20 was 17.1 per 100,000 males, compared to 6.2 per 100,000 females. This is down from 18.3 suicide deaths per 100,000 males in 2009. Over the previous 9 years, the trend was quite stable.

- Māori males had the highest rates of suicide between 2009 to 2023 of any group. In 2023, the suicide rate for Māori men was 21.7 per 100,000 Māori male population - about 1.7 times that of non-Māori males.

In 2023, there were 249 serious non-fatal injuries from self-harm reported in total. Of these, 129 involved males and 120 involved females. The numbers show a fairly even distribution between sexes, with males making up just over half of the total.¹⁰

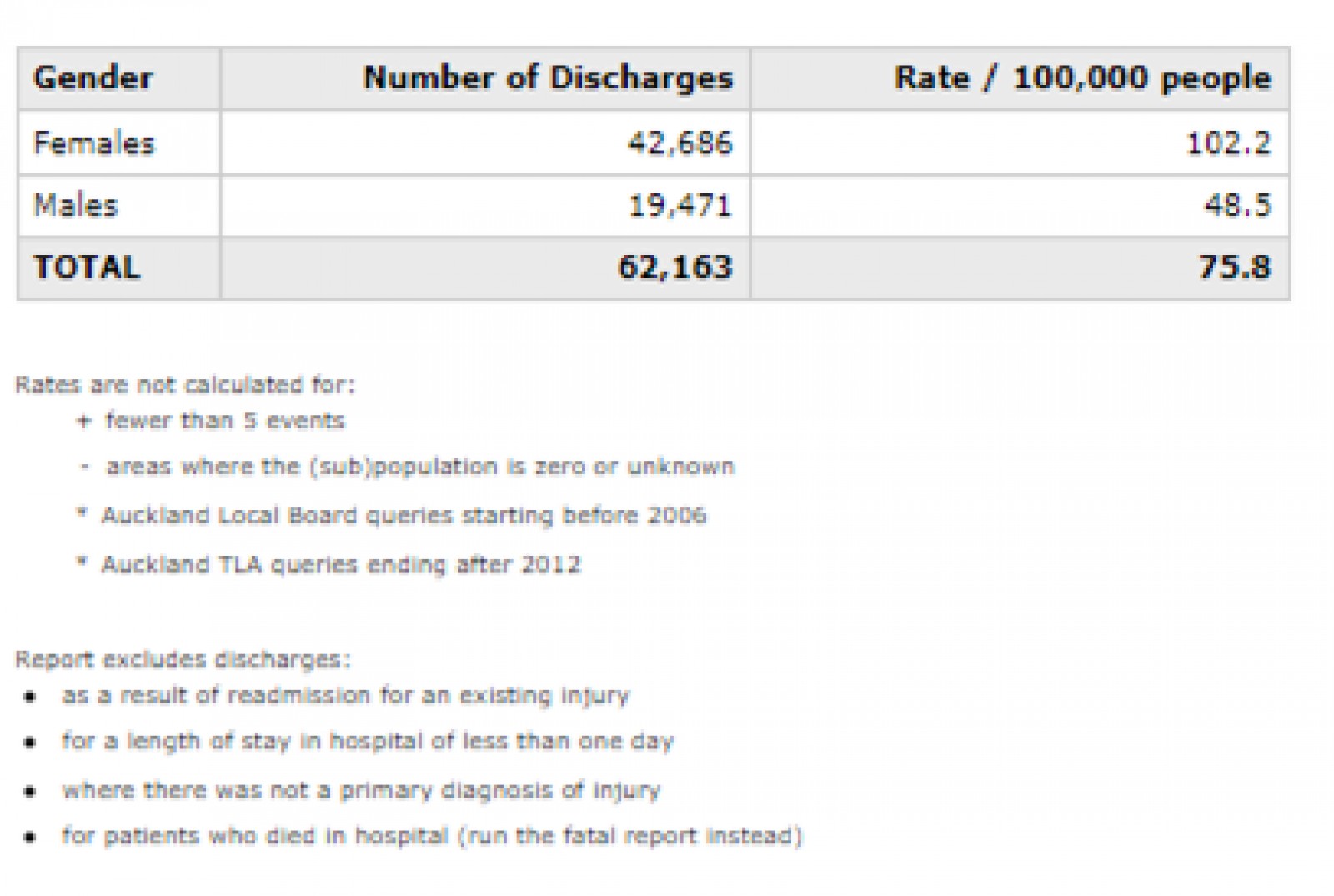

The table below shows figures for the NZ public hospital injury discharges between 2000 and 2018 for all external causes, self-inflicted intent, all genders, all age groups and all NZ.¹¹ Discharges for males are half those for females.

Wellbeing statistics

The wellbeing figures below are from the 2023/24 annual result in Ministry of Health’s New Zealand Health Survey¹² and from Statistics New Zealand’s 2021 General Social Survey.¹³

Life satisfaction and overall wellbeing

In the 2023/24 Health Survey, 83.6% of men report high or very high life satisfaction, compared with 82.8% of adult women. 3.0% of men report low life satisfaction, compared with 3.4% of women and 3.2% of the general adult population. The survey’s life satisfaction indicator has been collected since 2021/22.

Similarly, in the 2021 General Social Survey, 81% of people in New Zealand, aged 15 years and over, rated their overall life satisfaction at 7 or above on a 0 to 10 scale (where 0 is low and 10 is high). This is unchanged from 2018. The rating breakdown for gender was 81.7% for men and 80.5% for women. And an estimated 22.8% men report poor overall mental wellbeing compared to 33.4% of women.

Whānau family wellbeing

83.2% of men report high or very high family wellbeing, compared with 81.3% of adult women and 82.0% of the general adult population. 2.5% of men report low family wellbeing, compared with 3.5% of adult women and 3.0% of the general adult population.

Happiness

In the 2021 General Social Survey, an estimated 79.2% of men over the age of 15 felt happy the day before the survey was undertaken. This is slightly more than the 76.5% of women.

In another view of the same survey, an estimated 60.8% of men felt cheerful and in good spirits all or most of the time in the two weeks prior to the survey, compared to 58.3% women.

Finances

An estimated 7.5% of men report they do not have enough money to meet their everyday needs, compared with 10% of women.

Risk and protective factors

Risk factors for men’s health more generally include obesity, hazardous alcohol and substance use.¹⁴

The 2016 Social Survey found that as compared with women, men are more likely to be potentially hazardous drinkers or to be injured at work or on the road. Men are less likely to be unemployed, live in low-income households, report being lonely or experience discrimination, or be hospitalised for self-harm or attempted suicide.¹⁵ ,¹⁶ Although young men, especially Māori and Pasifika men, are at higher risk of unemployment.

A recent study on New Zealand young rural men’s mental health¹⁷ presents the following protective factors:

- Social connection

- Mindfulness

- Nutrition and Exercise

- Values

- Te Whare Tapa Wha

- Connection to nature

- Helping others.

Barriers to mental health support

Men are less likely to seek help.¹⁸ In the workplace for example, Australian research suggests that less than a third of men seek help for mental health issues. The research found that of the men who did seek help, only 66% self-referred (that is, they weren’t prompted by a partner).¹⁹ The New Zealand study on young rural men mentioned above²⁰ presents barriers in three categories: knowledge-based, shame-based and practical-based. Knowledge-based barriers include:

- the ability to recognise when a mental health issue has become a problem

- knowing where to go for help.

Shame-based barriers include:

- stigma-driven hesitancy about talking to a health professional

- sharing about mental health struggles with a parent

- a sense of stoicism and putting on a brave face that inhibits help seeking.

Practical barriers include:

- logistical factors in accessing services such as time, money and location

- service accessibility

- wait times

- disclosing to an employer

- a shortage of counsellors and psychologists.²¹

For more information

What being masculine really means for men’s mental health in New Zealand

Umbrella Wellbeing’s 2021 post on men, masculinity and mental health. Includes practical advice on how men can support other men’s mental health.

A New Zealand Aotearoa campaign and programme addressing men’s health and mental health issues.

An international programme with a presence in Aotearoa with the goal of reducing rates of male suicide. It has also contributed funds to some campaigns in the Mental Health Foundation’s suite, eg Farmstrong.

A resource for New Zealand men on depression, risk factors, how to cope with it and treatment options.

A programme addressing rural mental health in Aotearoa New Zealand.

References

For more information, contact research@mentalhealth.org.nz

Compiled by: Helena Westwick

Edited by: Caryn Yachinta

Updated: August 2025

- Stats NZ. (2024). National population estimates: At 30 September 2024. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/national-population-estimates-at-30-september-2024-2018-base/

- Stats NZ. (2024). Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2024. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2024/

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora. (2024). New Zealand health survey: Annual data explorer. Ministry of Health. https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2023-24-annual-data-explorer/_w_ad3b57075df34475ac054ee9e9f231d9/#!/home

- Ministry of Health. (2023). Health and independence report 2022: Te Pūrongo mō te Hauora me te Tū Motuhake 2022. Ministry of Health. https://www.health.govt.nz/publications/health-and-independence-report-2022

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora. (2024). New Zealand health survey: Annual data explorer. Ministry of Health. https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2023-24-annual-data-explorer/_w_ad3b57075df34475ac054ee9e9f231d9/#!/home

- Te Whatu Ora - Health New Zealand. (2025). Mental Health and Addiction: Service Use web tool. https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/for-health-professionals/data-and-statistics/mental-health-and-addiction/service-use-web-tool

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora. (2024). New Zealand health survey: Annual data explorer. Ministry of Health. https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2023-24-annual-data-explorer/_w_ad3b57075df34475ac054ee9e9f231d9/#!/home

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora. (2024). New Zealand health survey: Annual data explorer. Ministry of Health. https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2023-24-annual-data-explorer/_w_ad3b57075df34475ac054ee9e9f231d9/#!/home

- Coronial Services of New Zealand and Ministry of Health. (2025). Suicide data web tool. https://tewhatuora.shinyapps.io/suicide-web-tool/

- Stats NZ. (2024). Serious injury outcome indicators: 2000–2023. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/serious-injury-outcome-indicators-2000-2023/

- Injury Prevention Research Unit, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago. (2018). NZ Injury Query System (NIQS). https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/ipru/

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora. (2024). New Zealand health survey: Annual data explorer. Ministry of Health. https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2023-24-annual-data-explorer/_w_ad3b57075df34475ac054ee9e9f231d9/#!/home

- Statistics NZ. (2022). General Social Survey 2021. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/wellbeing-statistics-2021/

- Beaglehole, R. (2020). Men’s health—Risk factors [Web page]. Te Ara Encyclopedia; Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga. https://teara.govt.nz/en/mens-health/page-3

- Ministry of Social Development. (2016). Sex differences in social wellbeing outcomes: The Social Report 2016 – Te pūrongo oranga tangata. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/webarchive/20241209060357/https%3A/www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/

- Ministry of Social Development. (2016). Social wellbeing outcomes for females relative to males: The Social Report 2016 – Te pūrongo oranga tangata. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/webarchive/20241209060357/https%3A/www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz/

- p. 90-92. Wright, K. (2022). Barriers to help-seeking for mental health issues in young rural males. (Unpublished document submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Practice). Otago Polytechnic]. https://www.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/5858

- Gallagher, J., Tuffin, K., & van Ommen, C. (2022). “Do they chain their hands up?”: An exploration of young men’s beliefs about mental health services. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 51, 4–14. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE85803217

- Bell, J. (2021). Men still face stigma around getting help for mental health at work: Study. HRD New Zealand. https://www.hcamag.com/nz/specialisation/mental-health/men-still-face-stigma-around-getting-help-for-mental-health-at-work-study/258676

- Wright, K. (2022). Barriers to help-seeking for mental health issues in young rural males. (Unpublished document submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Practice). Otago Polytechnic]. https://www.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/5858

- p. 82-84. Wright, K. (2022). Barriers to help-seeking for mental health issues in young rural males. (Unpublished document submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Practice). Otago Polytechnic]. https://www.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/5858